Since our childhood, we have heard and read many stories. There are different kinds of narratives in which a story manifests itself- legends, myths and folktales. We often use these words interchangeably. But theoretically, they are different, albeit with many overlapping areas. The major difference between a legend and a myth lies in the evidence. The historical evidence matters in a legend, no matter how insubstantial it is. But in a myth, the story assigns newer meanings and therefore becomes of supreme importance.

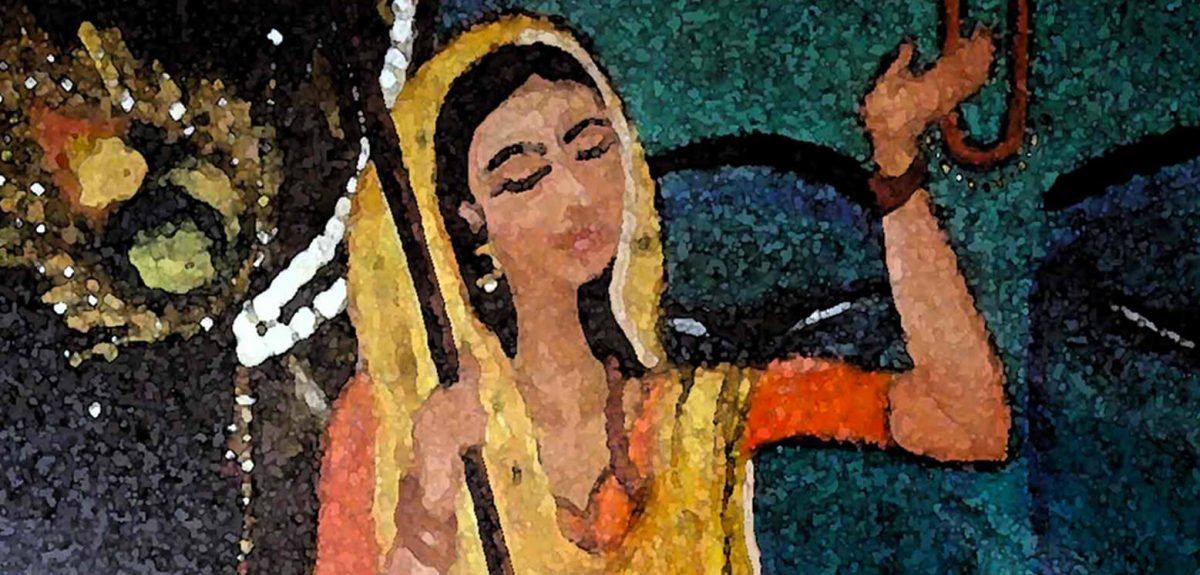

I recently travelled to the city of lakes, Udaipur in Rajasthan. While exploring the City Palace Museum, I found myself intrigued by the legend of Mirabai.

The story of Mirabai is a legend in that there is very little evidence about Mirabai that is authentic and is derived from secondary literature. It certainly includes some element of truth but has also evolved to have mythical qualities as it has been told and retold over different time, spaces and formats.

In the medieval history, Hinduism was facing growing ‘threat’ from religions like Islam. Many aspects of Hinduism made it less friendly and less accessible to the common man. While Hinduism was largely monopolised by Brahmins, Islam spoke about universal brotherhood and equality. Both consciously and unconsciously, the ideals of Islam produced a benevolent effect upon the minds of a section of Hindus and fostered the growth of a liberal attitude. In this backdrop and also with increasing Sufi influence, The Bhakti movement emerged as a response of Hinduism to making it more accessible to the common masses on the basis of values like love and devotion to get salvation from the worldly life.

Many sages and saints, who made Bhakti their principal theme and gave a call to people to worship in the simplest possible ways of devotion and love, became the torchbearers of this movement. This movement started in the South and soon spread across India.

Mirabai became an important figure of this Bhakti Movement in the 16th Century North-West India. Mira was born into a Rajput royal family of Merta. In her childhood, when her mother told the innocent Mira that Lord Krishna is her groom, she developed an uncanny devotion towards the popular incarnation of Vishnu and spent most of her time in worshipping him single-mindedly. Later on in her life, as a part of a strategic alliance, Mira had to unwillingly marry Bhoj Raj, the crown prince of Mewar. Her undying devotion to Lord Krishna garnered a lot of criticism from her in-laws. She was ordered to behave like a Rajput princess and was expected to take up the worldly responsibilities. But Mira’s devotion had no other purpose.

According to a popular legend, Mirabai’s in-laws tried many times to execute her, such as sending her a glass of poison and telling her it was nectar or sending her a basket with a snake instead of flowers. According to the hagiographic legends, she was not harmed in either case, with the snake miraculously becoming a Krishna idol (or a garland of flowers depending on the version). Yet another legend states that the Mughal emperor Akbar came with Tansen to visit Mira and presented a pearl necklace, but scholars doubt this ever happened because Tansen joined Akbar’s court in 1562, 15 years after she died. It is said that Mirabai died when she was 47 or merged with her god at Dwarka.

Towards the end of her life, Mirabai left all that held her back and all that forced her to live a life she had no interest in. She broke the Rajput social codes, took to the roads, travelled far, and mixed with all kinds of people, including those forced to live on the margins of the society. Her ‘bhajans’-poems through which she used to express her love for Lord Krishna, became their music too, something they still associate themselves with.

Mirabai’s contribution to the Bhakti movement was primarily in her music. Her songs express her love and devotion to Krishna, almost always as Krishna’s wife. The songs speak of both the joy and the pain of love. Metaphorically, Mirabai points to the longing of the personal self, atman, to be one with the universal self, or paramatma, which is a poet’s representation of Krishna. Mirabai wrote her songs in Rajasthani and Braj Bhasa languages, and they were translated into Hindi and Gujarati.

The Narrative of Mira in Pop Culture

Mirabai has become a cultural icon with her story used as a metaphor for women living life on their own terms, standing up for their rights in a patriarchal society hell-bent on putting them in a box.

In a documentary titled ‘A Few Things I know about Her’ directed by Anjali Panjabi, there is a mention of one of the many stories that have become a metaphor for the obstacles Mira had to overcome. It is said that because of her utter defiance to the existing norms related to the role of a woman in the upper-class Rajput society, she angered her father in-law Rana Sanga. He took out a dagger and rushed to kill her but suddenly there were a hundred Miras, which one should he kill?

As the legend of Mira was told and retold, its narrative resurfaced many times, in many forms- songs, paintings and movies and interestingly, pop-culture has ended up giving us ‘hundreds of Miras’…

The tune and lyrics of a very popular Hindi song ‘Rang Barse Bhige Chunar wali, rang barse’ from the movie Silsila, which is generally played on Holi in urban areas of northern India, are taken from one of the many folk bhajans written by Mirabai. However, the lyrics are slightly altered to mold the song into appropriate context of the movie script. First few lines of the original bhajan are

“Rang barse o meeran ,bhawan main rang barse.

Kun e meera tero mandir chinayo, kun chinyo tero devro..

Rang barse o meeran ,bhawan main rang barse”

In many regions of Rajasthan, bhajans of Meera are still common in religious night gathering known as ‘Ratijuga ‘ organized by women.

Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s adaptation of Devdas shows a meeting between Parvati and Chandramukhi, the two leading women of the narrative. While the original novel does not talk about any encounter between Parvati and Chandramukhi, Bhansali’s movie has a popular song called ‘Dola re Dola’ that becomes a defining moment in the movie as Parvati and Chandramukhi dance in acceptance of each other and their own fate.

The song has a line that says ‘Bandh ke main ghunghroo, pehen ke main payal’. There could also be a religious subtext to payal and ghunghroo. In many Hindu texts, it is mentioned that Krishna’s lover Radha used to wear flower anklets, and during Raas-Leela, the sound of anklets was heard. On the other hand, Mira used to sing bhajans in Krishna’s name with ghungroo on her feet; also popularized by the song Ke Pag Ghungroo Band Meera Nachi Thi from Namak Halaal. Earlier in Devdas, there is a song Morey Piya, in which the dance of Paro and Devdas represents the raas-leela between Radha and Krishna. Jamuna ke teer baaje mridang, kare Krishna raas Radha ke sang- On the banks of the river Yamuna, the drums are beating, and Krishna does raas with Radha. Paro and Devdas are Radha and Krishna. In the song, too, we see Paro, as Radha, wearing a payal. At a later stage, Paro visits Chandramukhi, and she sees Krishna’s idol in her house. Chandramukhi says to her that she worships Dev. Main toh sirf unki pooja karti hun. She tells Paro that for her, Dev is omnipresent, and if she sees through her eyes, she will find his essence in everything related to her. If Paro is Radha, who wore payal, Chandramukhi is the Meera who dances with ghungroo. Chandramukhi refuses to take ghunghroo from Kaali Babu, and refuses to dance for him. She waits for Dev to come because, like Meera, her ghungroo are for Dev.

It is interesting to note that the choice of their respective ornaments, that is Payal for Paro and Ghunghroo for Chandramukhi are connotative of their societal status. While Parvati was very well accepted in the society as a ‘Thakurani’, Chandramukhi came from a community that lived on the margins and was differentiated from the mainstream. While a payal is usually associated with a woman’s beauty and grace, ghunghroos have gained the reputation of being usually worn by courtesans.

Jodhaa’s character in Ashutosh Gowariker’s Jodhaa Akbar had a very strong reference to Mirabai. Jodhaa was shown as a Rajput princess who worshipped the idol of Lord Krishna. In the movie, after accepting her marriage alliance with Akbar, Jodhaa asks for a temple in his fort and continues worshipping Lord Krishna even after marrying into a muslim community, signifying the quintessential devotion that is instantly associated with Mira.

The uniqueness of Mira’s narrative is that it has travelled across the Indian subcontinent and beyond, not just as texts but also orally, as songs and bhajans.

Other than just Mira, the devotee, I think of Mira, the narrator – who travelled across the length and breadth of North India, cut across caste and creed, who chose the language of the people and told her story. Hers is a narrative, not just of devotion but also of resistance.