The conversation on sensuality drifted to a decade old Wild Stone deoderant ad. A steamy portrayal of a saree clad woman, in traditional finery, prepping for pujo bumps into a young man. Her imagination paints a sensational, passionate and visibly sataiting encounter. While the later cuts were censored on our TV screens, the sex appeal lingered on.

With plenty such characterisations and beyond, what’s with women of Bengal that they often come across as free spirited, free-willed and liberated? Even if marginally more than women from other parts of the country. At the outset is a discalimer: this may be a generalisation. Also, lopsided gender roles exist here as well.

One lens to decode culture is beliefs and mythology. Histories, languages and rituals intertwine around and shape our collective cultures. Massive Durga bhakti is evident, but what more can she tell us to make sense of our understanding?

Stemming from the reverence of Earth, fertility and the womb – the feminine divine/Nature has had a fickle equation across societies. Later sidelined in many of them, she’s largely relegated as the ‘mother’ in others. Shakti in Indian mythology, though has had fascinating stories, circumventing the trinity of Bhrama-Vishnu-Mahesh.

Associated with the three of them in her several forms and roops, the primal Goddess is most closely tied with Shiva. Sati, an avatar of Adi Parashakti (original supreme feminine divine) despite her father Daksha’s wishes married Shiva. The father-king not very fond of his naked hermit son-in-law, skipped Sati and Shiva’s name from an invitation list for a yagna at his place. Obstinate Sati had her way and reached the yanga. Following an altercation with her father upon her husband’s dishonour, Sati immolates herself. A furious Shiva is on a destruction spree as he carries his wife’s corpse and performs the tandav. In order to stop him from the pillage Vishnu shoots his Sudarshan Chakra and Sati’s body scatters in 51 pieces. Wherever they fell, the places became potent with energy. These are the 51 Shakti Peeths – the supreme seats of the Devi.

While most states of India may have two, three or four Shakti Peeths, Bengal has an astounding eleven and Bangladesh, six. The sheer density of these along with those of the neighbouring Assam and Orissa makes for a compelling reason to dig deeper – that could have moulded belief systems of Bengali women and men.

In contrast to the Shakti story of the headstrong Sati setting herself ablaze, is Ramayana’s docile Sita; who was decreed to agnipareeksha to prove her chastity. Popular deity in northern India, she models an ideal wife along with her maryada-purushottam husband.

As the prime Goddess, Shakti is the wife of Shiva in her many forms. After Sati (from the Vedic age), Shakti takes birth as Parvati (in the post Buddhist Puranic literature) who resolves to marry Shiva (the persistence quite a contrast to the day’s popular media love-chase). The idea is to transform the hermit to a householder. Vedic importance of yagna and fire gives way to Puranic puja and water – Parvati makes Shiva to break the flow of Ganga – she rejuvenates Shiva and the world. Her nudging transforms Shiva into Nataraj, their conversations are the source of all wisdom – stories, sensory pleasures and esoteric Tantras. [1]

Hence, the ritualistic form of worship, that cares not much for abstinence traces Shaivism and Shaktism. Several Shiv and Shakti temples have liquor as prashad, meat is prepared as an offering, animal sacrifice isn’t unknown. Tantra texts also hold the view of the world blooming from the union of Shakti and Shiva thereby celebrating Kama (love-making and the God of love). Marking the passion of Shakti and Shiva as the creation source of all life and death, several temples adorn explicit sculptures and art – a belief that all that is, is before the eyes of the divine. Therefore, perhaps the underlying essence of these rituals find stronger relevance to the believers of Shakti and Shiva – acknowledging all aspects of nature valid, contrary to Bhrama’s sense of ‘purity’.

Tracking tales from the temples

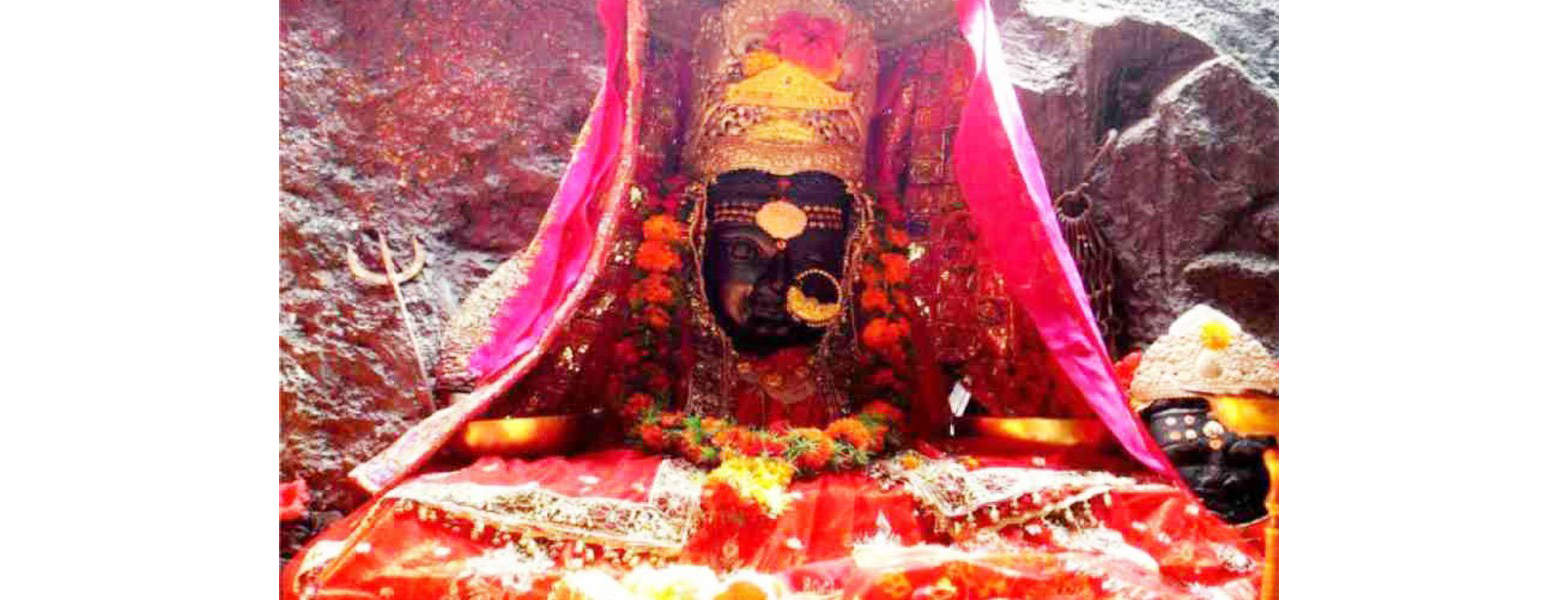

In Guwahati – the Kamakhya temple is where Sati’s yoni and garbh (vagina and the womb) fell. Understandably, one of the mightiest Shakti Peeths. The goddess of desire and fertility, Kamakhya literally means the conscious awareness of love (Kama ~ love/lust + aakhya ~ consciousness/wisdom). Lore has it, this was an amorous hideout for Sati and Shiva. Childless couples throng the temple offering the goddess animal sacrifices and red hibiscus flowers. In the month of June, the mighty Bhramaputra turns red for three days which as believers have it is when the Goddess menstruates. The actual reason could be the cinnabar deposits on the hill where the temple stands. The powerful goddess has been worshipped since time immemorial as a gramdevi (village goddess) before being included in the Hindu pantheon as Shaivism expanded in the region that is today Assam.

Shakti’s stronghold is Bengal. While Amba, Rukmani, Meenakshi and other roops of the Goddess are worshipped in other regions, she’s often worshipped there along with more popular Gods – Vishnu or Shiva or their forms. Punjab and Jammu have Shakti following in the form of Sherawali Maa or Vaishno Devi, though her manifestation is starkly benign, a smiling mother – possibly a gramdevi adapted to the imagery of Durga. One of the reasons could be the perpetual invasions, interaction and intermingling of cultures in the region of Punjab that the earlier versions of the goddess may have waned.

Durga is all encompassing, an amalgamation of the powers of Bhrama Vishnu Mahesh – the prime Shakti, risen to end evil. Mahishasura – a buffalo-human devil had a boon that no man or animal could kill him and hence the fearless Durga manifested, Durg translates to a fort or invincible.

Resounding stories of her valour are celebrated throughout pujo, the biggest festival for Bengalis. Durga here is a daughter, visiting her maiden home on Earth and hence celebrations must know no bounds. There is no sanction on alcohol or meat or fish – which otherwise are impure during prayers to other deities.

Iconography of Durga distincts itself from the mother-goddess worshipped elsewhere. Her autonomy with her ferocious lion/tiger vaahan is more dynamic here and she’s not simply seated. Starkingly away from other goddesses, her hair is loose and free-flowing – unrestrained. Remember Draupadi – who’s veritable woe was her being dragged into the court with her hair untied – a great dishonour. The inherent belief that women’s hair should be tied in place – which is traditionally desirable, Durga demonstrates women to be, untied, unrestrained and untamed.

Sringaar, dear to the goddess explains the deep kohled eyes, bigger bindis, and sindoor. Sindoor khela during pujo celebrations is where women smear it on each others’ faces is distinct to the region. Chemically, sindoor is made of turmeric, lime and cinnabar (mercury). Physiologically it is believed to keep one’s blood pressure in check and enhance one’s sexual apettite. While this attempts to explain its fertile importance to married women across India, the festivity of it in Bengal perhaps sets the tone apart to the celebration of female energy of Durga.

The untied hair and the bridal finery keep Durga at the cusp of free-willed Nature (essence of Shakti) and rule-led culture. [2]

While Durga is worshipped in pandaals through the nine day festival, it is really Kali who is worhsipped in temples across Bengal. One of the other more proiminent Shakti Peeths is Kalighat in Kolkata. Kali is one of the das mahavidyaas (ten great wisdoms) of the goddess. Her story is about a demon called Raktabij who cloned himself with every drop of his blood that fell down. Kali was summoned to tackle him and she does, she drinks his blood till the last drop as he drops dead.

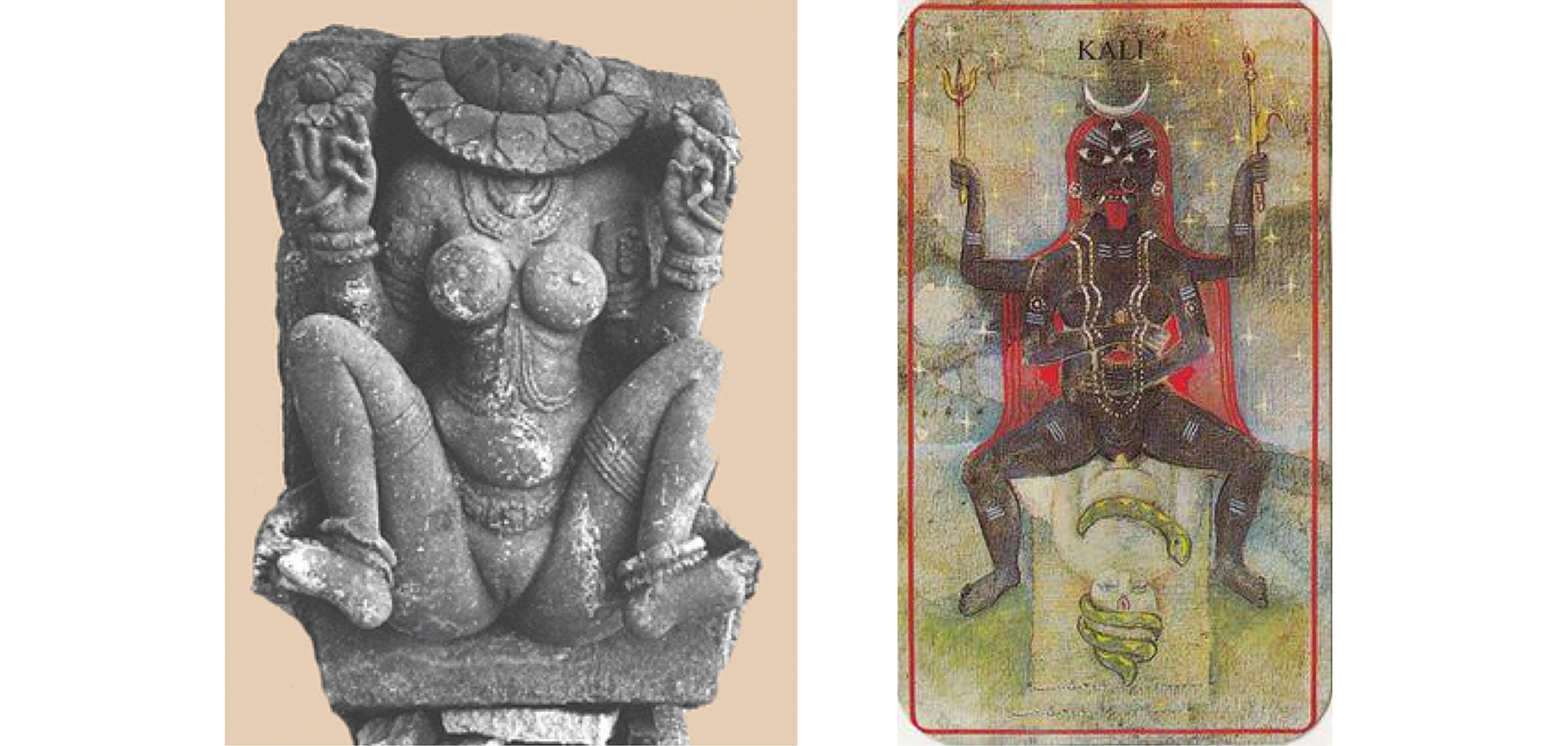

Kali is the feminine of Kaal (Shiva) which means time and death. She is Nature, which existed before culture took birth, and will be beyond culture. Her depiction as dark coloured goddess grew along with the idea of the infinite being mysterious. She consumes all life and is fierce. Her imagery conveys the decapitation of ego in the form of Raktabij’s head that she holds. The human hands that adorn her waist is the killing of rage, while her voluptuous breats are sexual and nurturance. The nosering is conspicuously absent – a traditional marker of domesticity. Her hair is matted and unfettered. Her nakedness connotes carnality, purity and nature in its raw form. The tongue sticking out is the distinct iconography of Kali.

Certain Shakta literature narrate how Kali not only steps on her husband Shiva, but nudges him to make love to her. Nature nudging man to acknowledge, care and pay attention to the other, including nature. Shiva and Shankti stories have how sages bump into them making love which is why the sages decreed Shiva to be worshipped only as a ling. One version says how Shakti is embarassed and she covers her face with a lotus flower. The version gave rise to Lajja-Gauri; the other is where Shakti sticks her tongue out daring the sages’ disapproval, or deriding them for they are judging nature. Kali’s tongue that mocks the finiteness of human gaze changed meaning through centuries and during the colonial era become more ‘sanitised’ as per Victorian moralities. [3]

The now popular story (evolving through 18th-19th century) is about shame of having stepped upon her husband Shiva who lies beneath her so as to stop her from her devastating frenzy. The other is really lust for more to destroy – blood from the animal sacrifice is at some temples, smeared on her tongue.

Contrast the Devi with her more motherly roles being worshipped in other regions. Her other raudra roops that depict her sovereignty and true to nature forms such as the blood drinking Chinnamasta upon a copulating Ratti and Kama have largely been sidelined in their native regions such as the Himachal. Between Vishnu, Shiva and his sons, and their popular avatars or forms, the feminine is mostly roled into the dutiful Sita, gentle Gauri, her avatar as the royal warrior Meenakshi marrying Shiva, or the chanchal Lakshmi who is either by the side of Ganesh or that of Narayana. Saraswati has her set of niche worshippers. Radha emerged only in 13th century Bengal and Orissa and eventually becoming popular in the Hindi speaking northern states. Yet her more emancipated, Nature/Kali-alluding, clandestine, night-time forest fantasies have somehow been veiled just as her head-covered portrayals through the medieval ages.

If our stories and mythologies shape our cultures, the immense popularity of and devotion to Kali and Durga forms the belief system of Bengali men and women. We do idolise our idols.

[Another lens to look at why perhaps the women of Bengal are relatively more free-willed, is the region’s captivating modern history, the rise of reformers and early Indian feminist thinkers/writers through Bengali renaissance. Does their genesis too lie in Durga? Stay tuned for part 2.]

[1], [2], [3]: Devdutt Pattnaik’s texts including 7 Secrets of the Goddess