The dust has settled. Along with the jury came a flurry of opinions, critiques and memes. Fair & Lovely was in a Catch-22 situation. Millions bought into it while its purpose itself has been its nemesis.

Cashing in on consumers’ deep seated insecurities, Fair & Lovely has reluctantly shed its misogyny (kash hume beta hota ad), and colourism – having equated fairness to success. With such massive revenues (massive brand following), revamping would mean losing the brand altogether. And hence to rename the brand with the same purpose (to latch on to the same audience) it was expected they’d retain its recall value – ‘&’ sign or the colours. And that’s precisely what happened – a glowing cosmetic change to Glow & Lovely.

Glow or nikhaar is something that they’ve built an equity with, over years, as a hook – it is now almost synonymous to gorapan (fairness). Ways how language works, it morphs over time. And that’s precisely where colour problem (like most other issues) is rooted.

If we seek fair wives in our matrimonial ads, and skin lightening products across price ranges, it runs deep in our culture. Cultures are manifested through language. We’ve grown with apologetic lyrics of ‘hum kaale hain to kya hua dilwale hain’ and compromising descriptions like ‘sawali par sundar’ (~so what if I’m dark, I have a heart and dusky but beautiful). Teasing someone with the words ‘kaalaa/kaali’ is ridiculing someone for their truth itself and not an attached attribute. What are our deeper beliefs around darkness or blackness that create the bias?

We may not realise, but our everyday communication is replete with phrases that embolden the bias. From blacklist to black money / kaala dhan – which are something unacceptable and illegal respectively. From muh kaala karwana or kalmoohi, to buri nazar wale tera muh kaala. Or the idea of splashing someone’s face with ink on a public platform (relegated to many politicians), or chunri mei daag lagna – all revolve around the idea of being defamed and dishonoured. Once blacklisted, redemption isn’t easy. Muh kaala karwana meant losing one’s prestige and honour and therefore the desire to be honourable comes with the opposite of kaala – white – which is untouched, which is also pure.

Hence, the idea of touched/tarnished or kaala being impure. It is in the same vein that one says, rang saaf nahi hai (colour isn’t clear) – as a corollary to getting maila/dirty. This trickily entwines the idea of low prestige or defamation with manual or menial labour ~ skin over exposed or overused or not having been taken care of. Language speaks volumes about where our inherent biases lie.

Mann kaala hona (black-hearted), or the Black Hole that consumes in all stars, or everything else when used as an analogy; or even Goddess Kali – which is unbridled Nature juxtaposed to her graceful Gauri roop who is domesticated, tender, motherly and fair. Kali Yamuna as opposed to gracious Ganga, and Kaal itself. Kaala is also apshagun (bad omen). Black or dark ends up being a vast mysterious space which is incomprehensible. And unknowns are often frightfully seen with apprehensions? Often, relatively dubious as opposed to a more willing assurance of the lighter? A kaala tika protects the vulnerable – darkness to ward off darkness.

Black is also luxury, dark being premium – and yet again the opposite being simplicity ~ reliability. Black bikes are macho and black dresses glamorous, making black (in certain mindsets) rebellious, and disdainfully alpha and vain – something that does not go down well with the conservative understanding. (Black being powerful and stable are only secondary codes usually reserved for objects.) Besides being portrayed such in popular culture, it is an inherent idea of tamsik – actions taken disregarding consequences. (tamas: Sanskrit – darkness) as opposed to sattvik – the lighter of the three gunnas according to Samkhya, that of balance, harmony, goodness and the likes.

Often, darker hued gods are now painted and sculpted fair. Several TV programs cast a fair Krishna (the common noun meaning dark). Blue being only a consolation. Mythologist Devdutt notes the worldliness of the dark Krishna – full of life – lover, dancer, warrior from the banks of dull kali Yamuna contrasting with an exuberant fair Ganga and her ascetic Shiva – Karpur Gauram – white as camphor.

So it is in our deep subconscious minds where over centuries we’ve learnt to disregard the dark – attaching either subtle or overt notions of hierarchy, or disgrace or unreliability. Unfortunately, the positive bias of darkness (the worldliness of Krishna or the raw prakrit / Nature of Kali) has long faded – layered with repetitive negative biases.

While businesses need to be socially responsible just as everyone else, increasingly so given their massive media spends and power of influence, it is really for us to unearth deep rooted prejudices within. Blacklisted could be ‘excluded’ or ‘debarred’. And even though ideas about shame anyway need a rehauling, our popular culture cries could switch to crisper badnaami than muh kaala karwana.

#culture #semiotics #fairandlovely #colourism

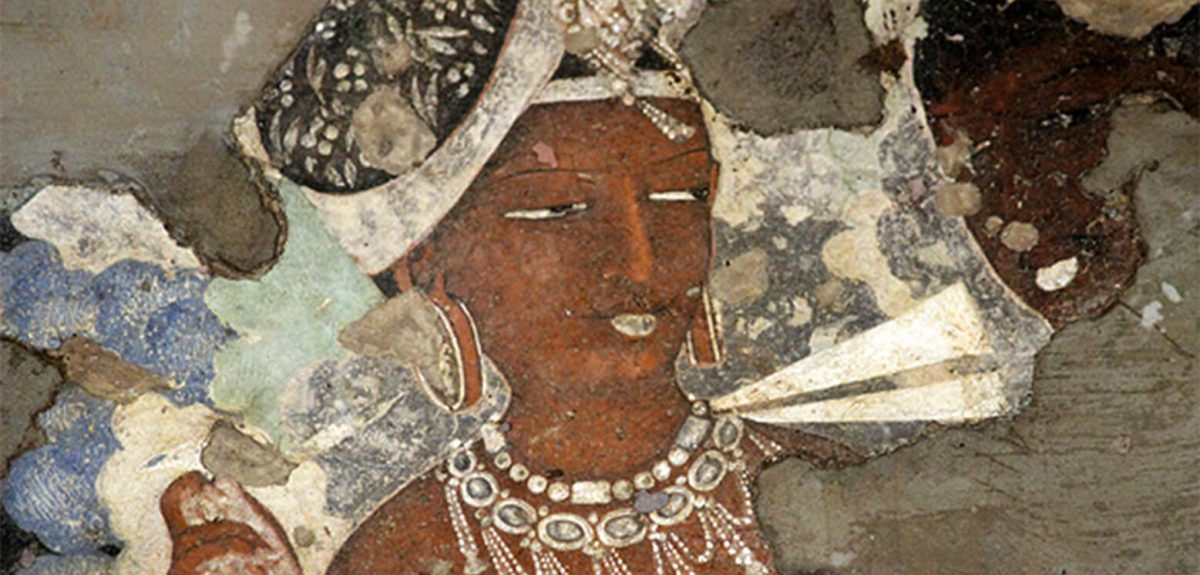

(Banner image: Apsara (Celestial Nymph), Ajanta Cave-17, 2nd century BCE to 1st century CE; Wiki Commons)