2010s has been a digital deluge for our social lives that changed much. Amongst other things it changed our sense of self – putting our identities in flux.

Who are we? How do we introduce ourselves now? We had often been introduced as sons and daughters of our parents (mostly fathers), who could be traced in extensive family trees, or through the bahi-khatas at holy Haridwar. We were bound to generations of our lineage. It’s akin to be modelled as our mythological characters, introduced as Gangaputra Bhishm, Devaki Nandan or Pavanputa Hanuman.

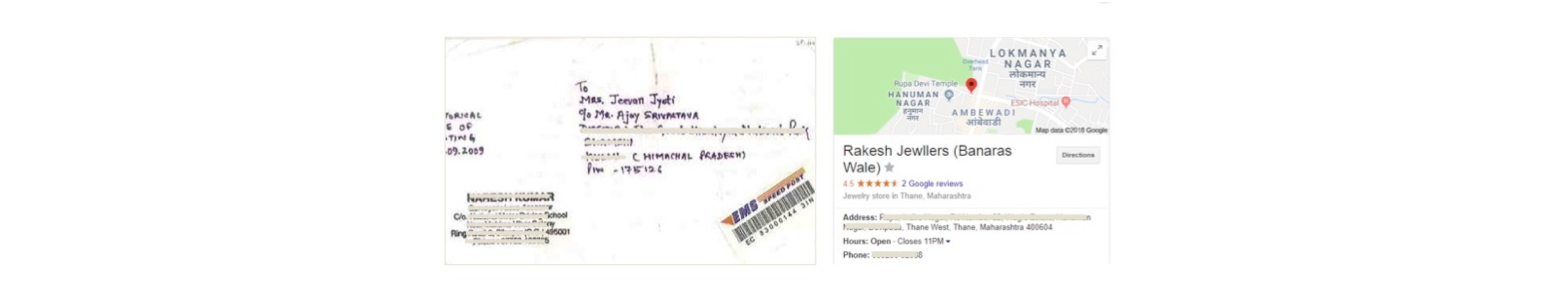

There has been a nexus of family relations – even as we moved from joint families to nuclear ones to individuals. Our introduction has largely been by association – as the son or daughter or nephew or niece of so and so. And our languages are coded to give specific names to this plethora of relations – a maternal aunt versus a paternal aunt. (And the types of maternal aunts and others – a mami and a mausi). C/Os and S/Os or W/Os for correspondence and locating one to a ‘bua ki beti’ has been our everyday language.

Friends too are an association – a friend from college or a friend from one’s hometown. Hometown, in fact has been another crucial marker of our identity. The family belongs to a village or a city. We recognise people as ‘Surat wale’ or ‘Bathinda wale’, or bua ki beti is more specifically, ‘Bareilly wali bua ki beti’. So much so, one may belong to a particular landmark as one’s identification – ‘the ones who stay behind the post office (insert: other landmarks)?’

Family by itself is one’s socio-cultural identity – language, caste, class all rolled into one, a package that clings onto us at our birth. With our family name comes what language we may speak, which region we may belong to, where we could be placed in the traditional social hierarchy and even an impression of what we may be basis our familial reputation in local communities.

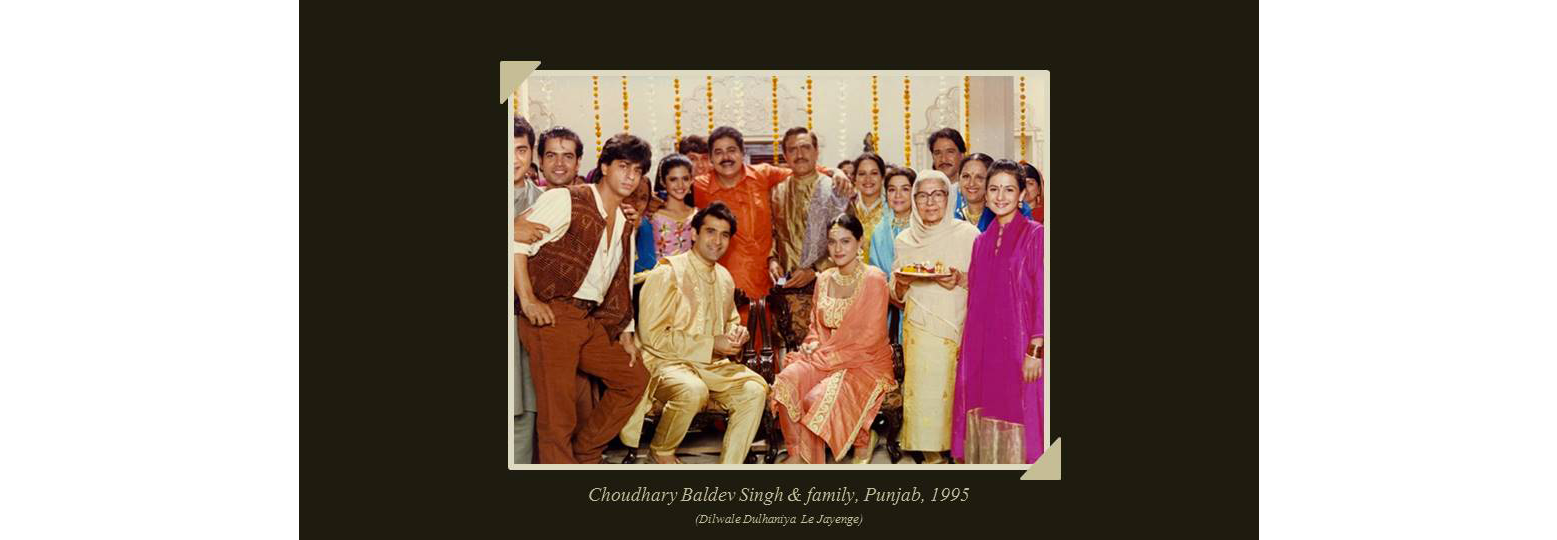

The good old wedding cards spoke more about the two sets of parents than the bride and the groom. It located grandparents, hometowns and often even the family occupation/business. Which brings us to third pertinent marker – the family business – ‘joote wale from Agra’ or ‘ball bearing ones from Rajkot’.

Traditionally our identities are given to us by human relationships, spatial relationships and professional relationships. But social media is changing our identities from ‘we’ to ‘me’. These platforms with specific ambitions are designed such that collectively they are altering our sense of self.

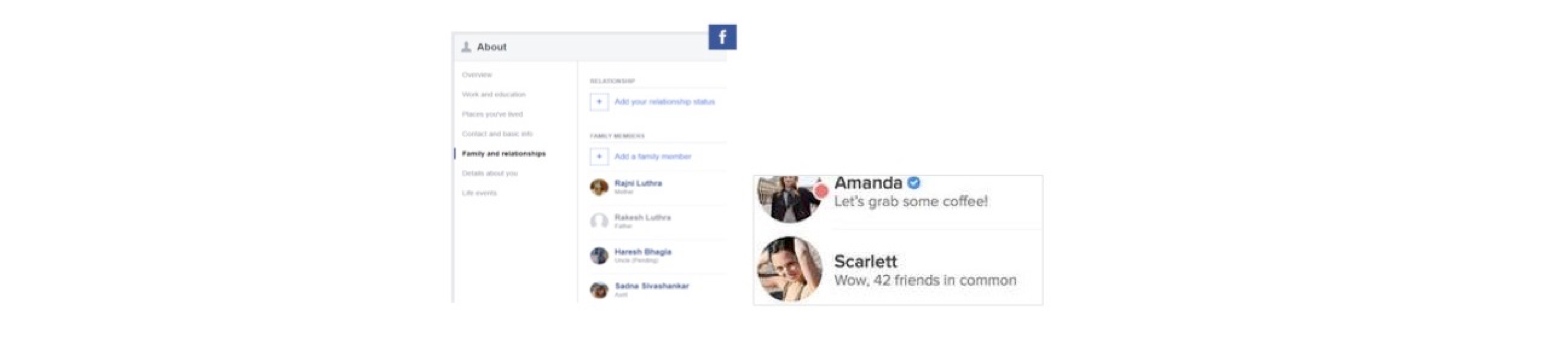

To begin with our identity through our family is waning – that entire package is disappearing. Facebook may nudge you to mark your family relations but they are hidden in deeper pages. Mutual-friends are now only a sliver of association. Facebook is 2006, the newer ones aren’t designed to designate family or friends and followers are unrestricted on open networks. In fact Tinder delinked Facebook mutual friends, while Snapchat has no common links.

Those lengthy registration forms are history. Location/City that has been a key identity marker is fast vanishing. Facebook and Twitter have non-mandatory location fields in their forms. One needs to dig in buried pages of a profile to fetch Facebook’s hometown just as its family members. Instagram’s design doesn’t deem it important, skipping the column altogether. And Snapchat and Tinder work on live location – to access content and people of that moment. I don’t really know where you come from.

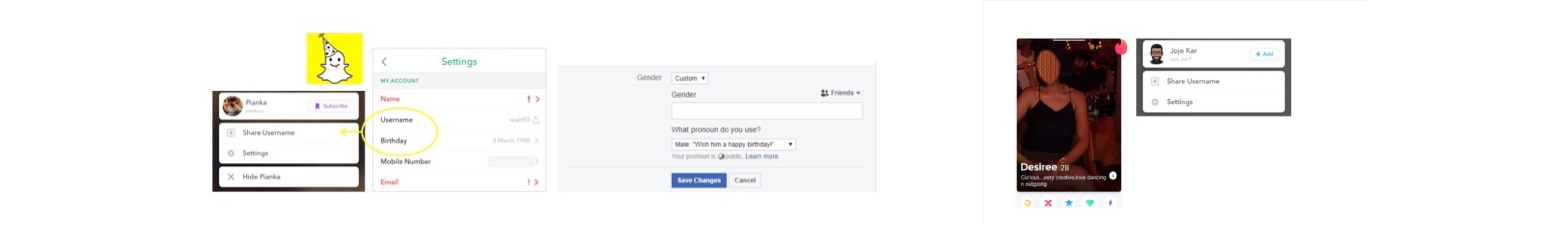

From a time when general introduction, even in books and stories were about an estimation of age, today it doesn’t matter how old one is. Older networks Facebook and Twitter have an optional column for age, while Facebook tweaked its design to display only the date and month of your birthday without the year. Snapchat uses it for registration without making it visible while Instagram’s sign-up forms reinforce that age is redundant today.

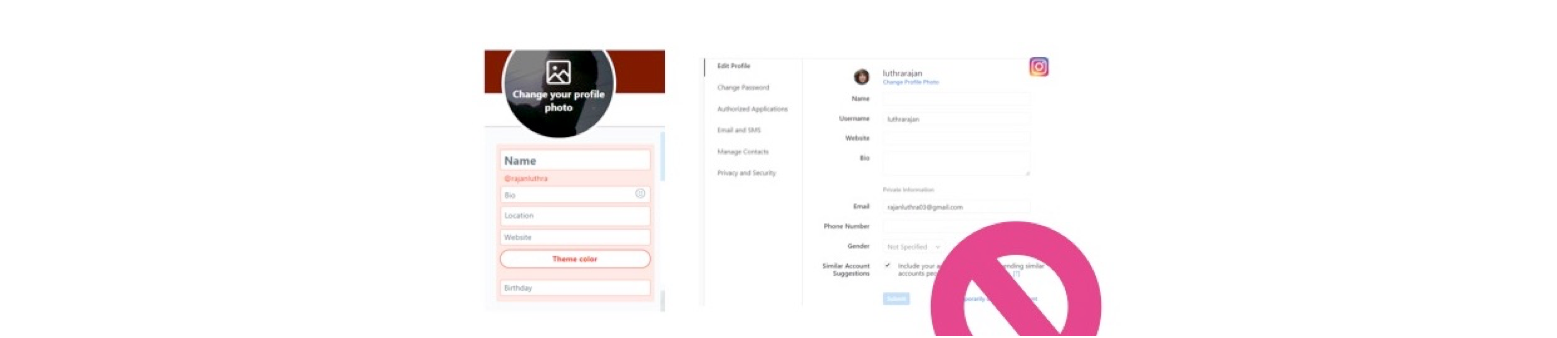

Talking of individual autonomy, Facebook’s new design allows one to customize one’s gender while Twitter, Instagram and Snapchat are designed un-gendered. I follow a brilliant painter on Instagram, whose posts are but only art – don’t know where he or she is from.

Sharpest is the shift in names. From our given names and adorable nicknames by family and friends, we’ve come to choose our usernames. Twitter’s UI still prioritized names over Twitter handles. But you could fly with any name such as ‘twotablepoonsbournvita’ or ‘neveragreatphoto’ or ‘MojoJojo’ on Instagram or Snapchat. In fact our pictures are our primary identity on Tinder, the deciding factor for one to be swiped either way. Pictures – where we’ve learnt to identify ourselves with best profiles, desired touch-ups and choose our favourite filters, shape shifting on our moods.

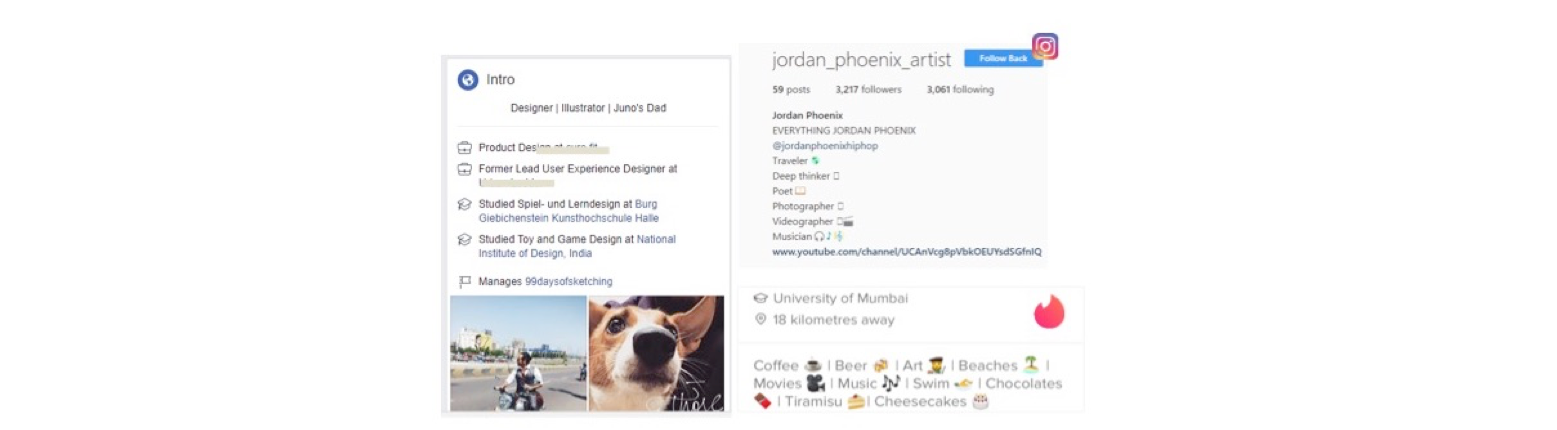

Through the decade, digital user experience designs have been worked upon such that it has rid itself of all, save a space for us to own. A space where we choose to introduce ourselves the way we desire. ‘Intro’s, ‘Bio’s and ‘About Me’s encourage us to define ourselves, explore ourselves – as our profession – ‘culture strategist’, or introduce us as our pet’s dad, or a thinker, photographer, videographer all in one, or just interests listed out – coffee | books | swimming | movies | tiramisu. In fact the self could morph into interests so much so that there is no self – only the subject of one’s interest – a page of our pet cats narrated in their voice. Is design giving us the space to assert ourselves?

Behold! Snapchat has no place for ‘About Me’. One can only see one’s posts – short, few hours lived posts. With no intros and bios, forget age, gender, place and the others, design has enabled us to flee all markers of identity. These vanishing stories are our identities. Soon caught on by Instagram and Facebook and even Whatsapp the short stories feed our need of impermanence – reflecting the switching behaviour of millennials – binging today, dieting tomorrow. These are our transient identities.

We do not want to be tied to a single identity – my Friday evening identity could be very different from my Monday morning one – the self, morphing onto design that would only bolster the idea of a version of me. Digital platforms are being designed to help us abandon the fatalities of our given identities.

The tacit restrictions upon us – repeatedly reminding us of being bound by something we are just born into. The idea of “what will be, will be” the baggage of lineage is being shed – expectations of us, and how we expect the trajectory to be. Our chosen identities are scribbles on white boards – they are our play identities allowing us to explore and switch. “Whatever can be, I want to be”. It frees us to reinvent ourselves, perhaps coaxing us to be more risk taking – generously encouraging us to script our own lives.

With the traditional tags of age, gender, class, religion, caste, language dropping off, and living an ecosystem online, perhaps over the decade our sense of self has metamorphosed into what we can make of ourselves, nudging us to assert ourselves, explore ourselves and liberate ourselves.

This was earlier presented at Semiofest 2018