An indistinguishable clutch of film actresses in varying shades of lime advocate green tea, hoardings hoot healthy oats, popular songs popularize size zero and milk cartons come with measuring tapes – these are visuals that hound us today. If being ‘in-shape’ keeps us so occupied today, it’s rather intriguing to have a glimpse of the visuals that spoke to our great-great-grand parents more than century ago.

A recently concluded month-long exhibition at Mumbai’s Bhau Daji Lad Museum curated by the renowned art and culture historian Jyotindra Jain was a pool of stimulating visuals – calendars, postcards, prints and insert cards. Mapping culture through visuals goes beyond advertisements. And in an age of nascent photography and a revolutionizing printing technique, paintings made the dominant visual form – the springboard for early advertising. The collection is a treasure revealing much about late nineteenth and early twentieth century India – its conscience, motivations and aspirations.

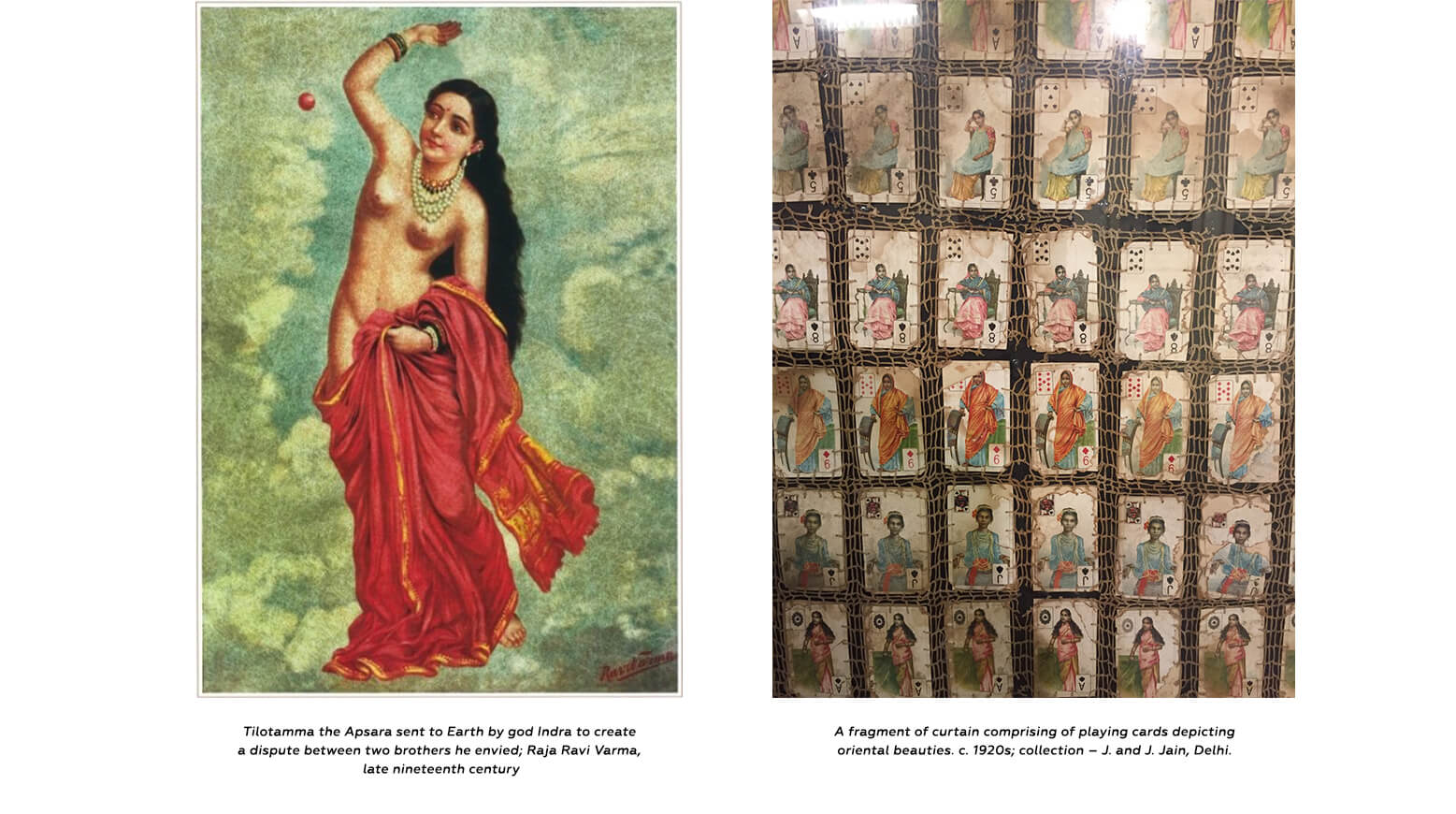

To set the context of time – traditional (flat and idealistic) painting was dramatically being influenced by European techniques (oil) and styles (realism and perspective). Raja Ravi Varma rendered ancient Vedic folklore and Hindu mythology with European realism – something unseen so far. And his printing press made art descend from the royal court to commoners’ roads. Almost suddenly, Hindu households had a face to their Gods.

Visuals spoke – the grandeur of Hindu mythologies, fine emotion of its characters and the elaborate episodes of the epics. Decoding the renditions of the Pauranik episodes brings out the immediate social environment of the times. Stories and subjects lifted from the Vedic age often got depicted in settings that were a confluence of Mughal and British influences, the day’s culture – popular clothing and fanciful settings of nineteenth century.

Shantanu, the Kuru king is shown wearing a Jama – a Mughal (or medieval Rajput) garb that of a tight fitting frock flaring up at the waist with a chooridaar, instead of the prevalent Vedic dhoti. So is the heavily embroidered footwear.

An early twentieth-century painting titled ‘Wedding of Rama’ by M. V. Dhurandar has women draped in contemporary Marathi styled saris and men sport the Mughal court costumes. In fact the landscape gives a hint of several temples and mosque domes lined in the background – an easy mix of the time which is a sharp departure from today’s soon emboldening divisive religious lines.

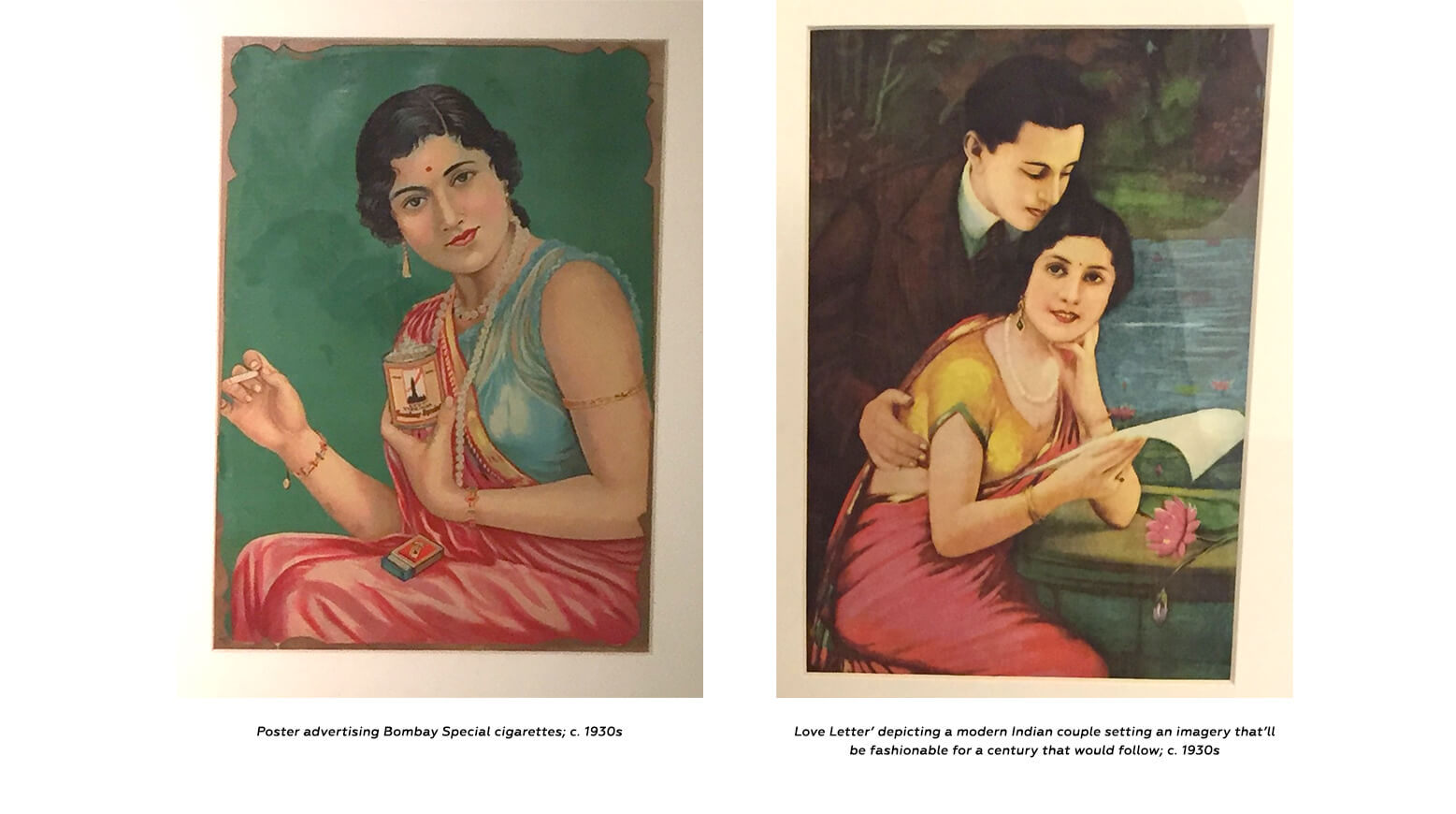

Along with his contemporaries, soon the sacred stood dangerously close to the sensual. The male gaze (continued from the translucent women’s garments from Mughal and Rajput miniatures) got accentuated by the realism corporeality of the new style. Semi-nude heroines from mythology became muses as an idealized white-skinned Indian woman, a standard slowly being laid down for future generations. From prints to playing cards – a collection with each depicting ‘Oriental beauty’, the gaze has passed down over a century.

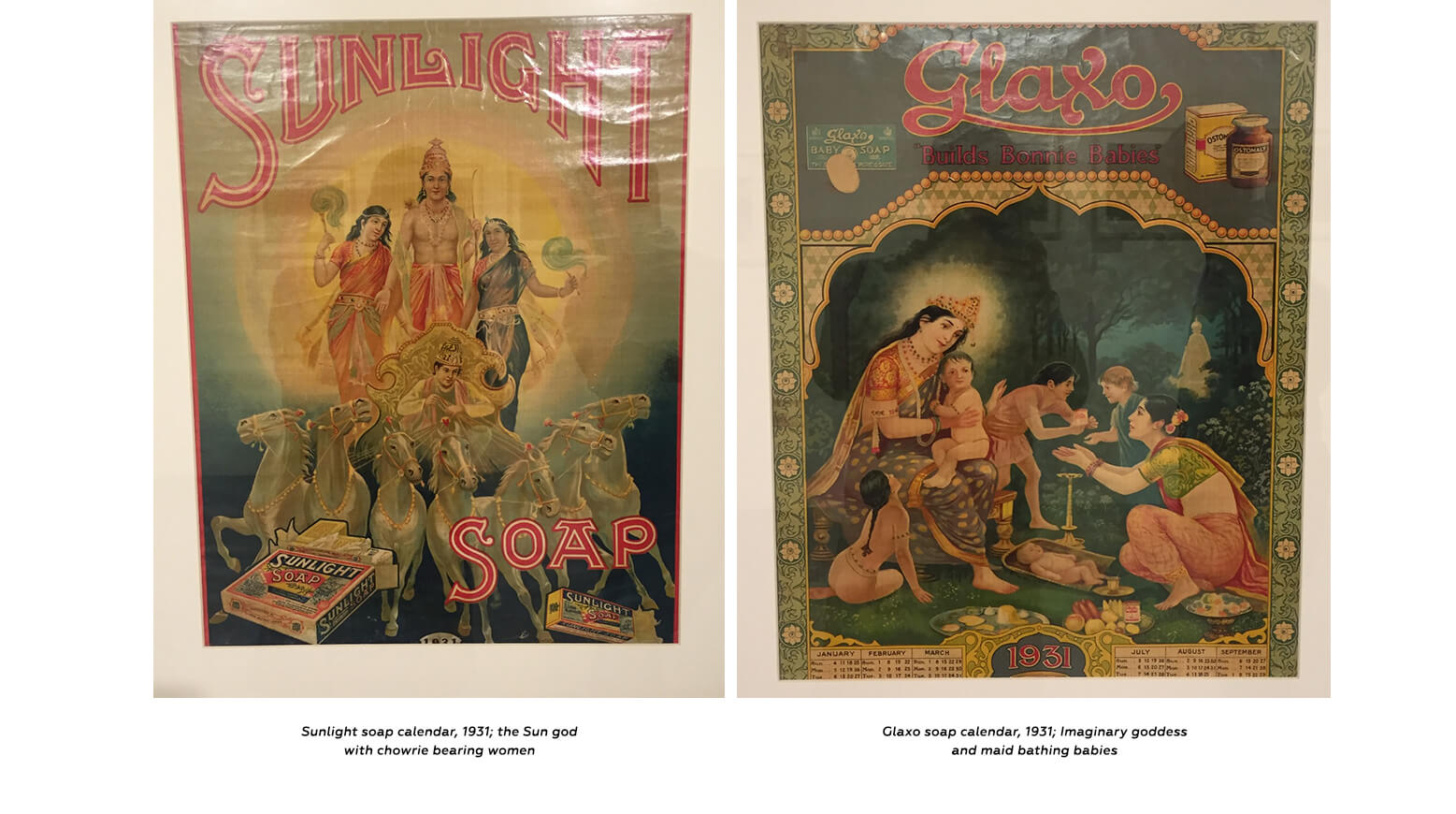

Soon after, with prints rolling out, these visuals became popular culture. In 1888 when Lever Brothers’ Sunlight soap disembarked on a Calcutta port it perhaps had no idea of how it would get reinvented to further forge a ritual with Indian masses. The Reverend Sun lord descended to sell the humble soap bar quickly followed by Pears, Lux and Vim.

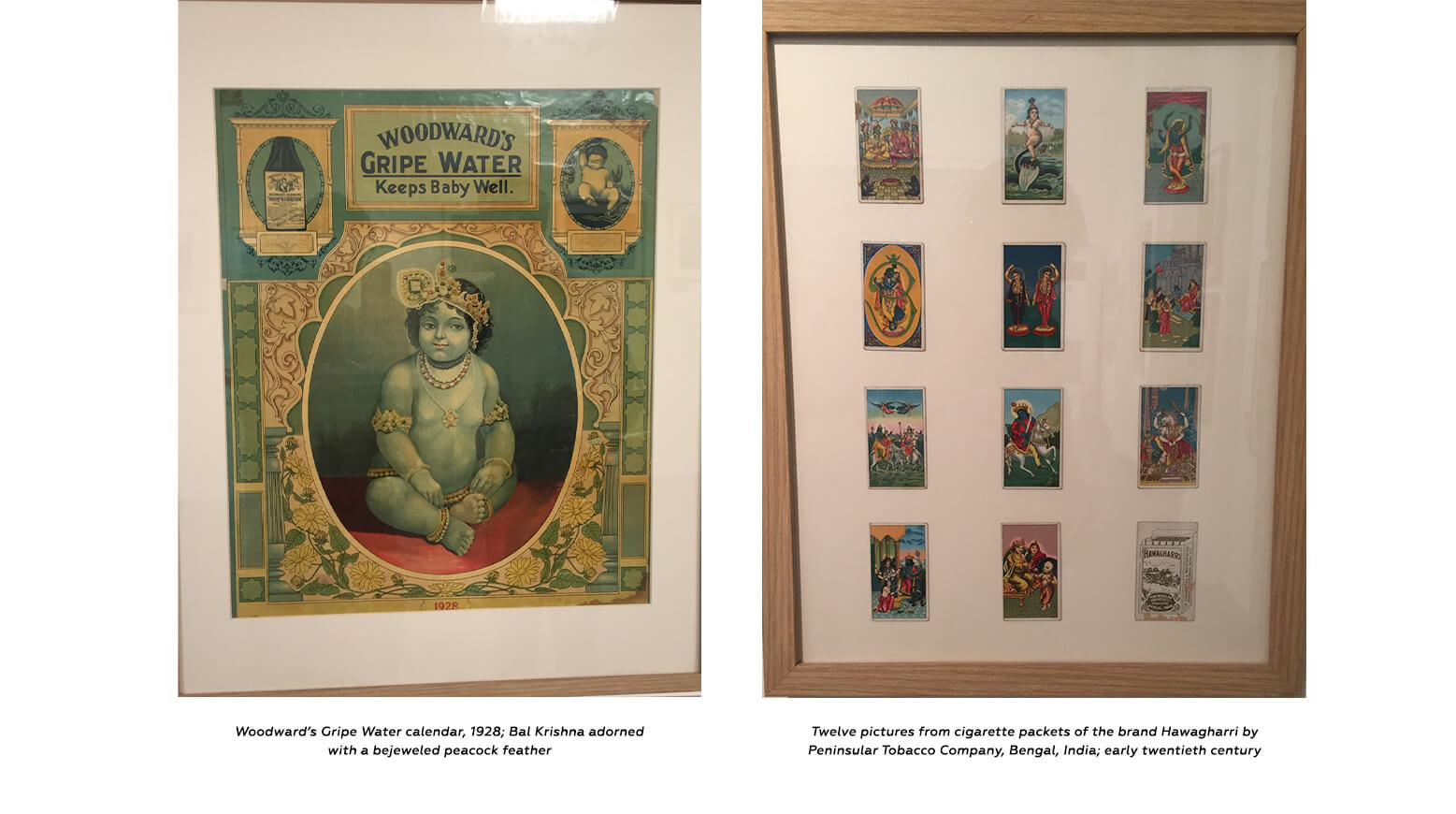

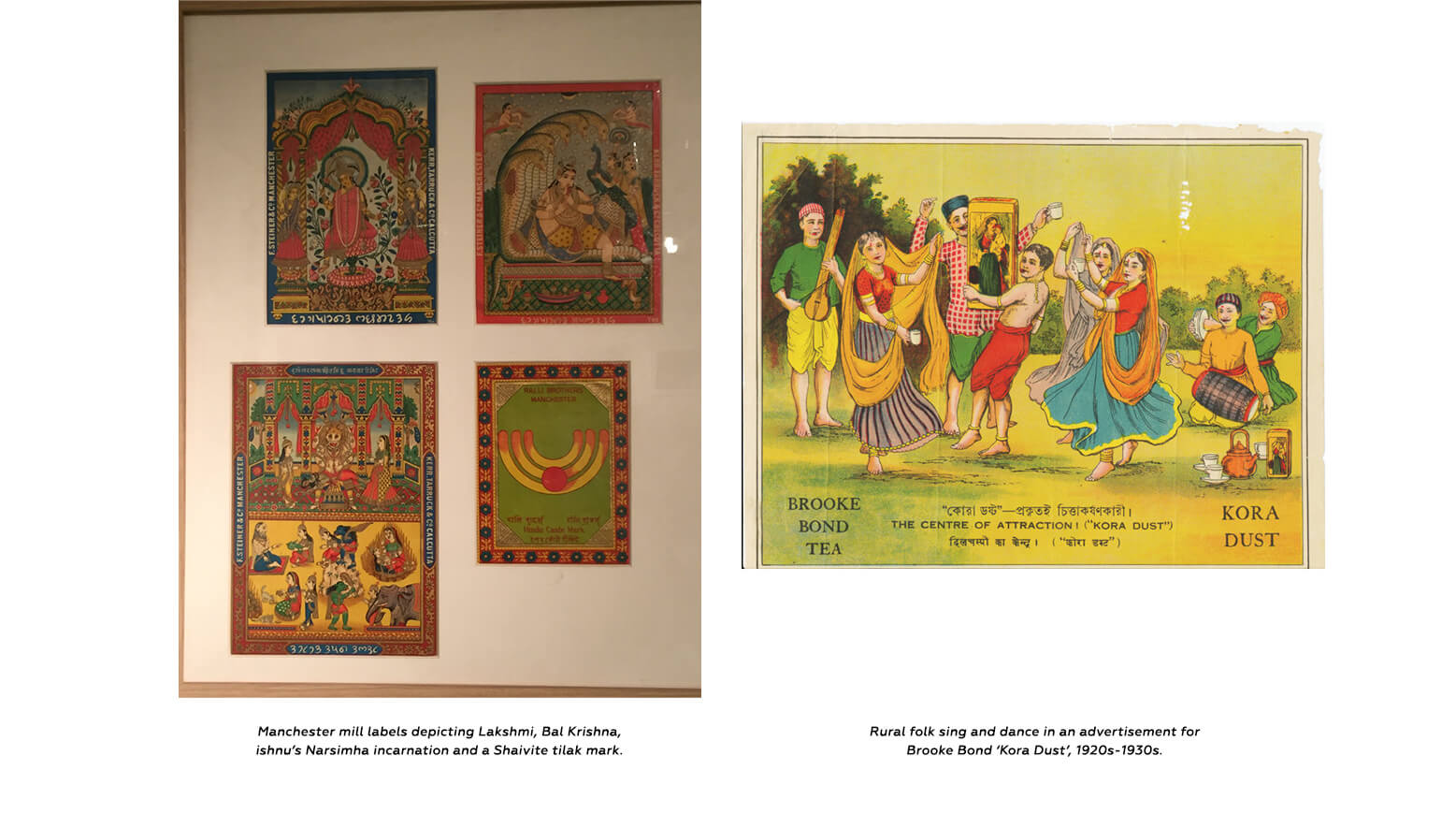

The army of Hindu gods and goddesses became brand ambassadors a hundred years ago, with each brand competing to have one. Bal Krishna made sure mothers bought Woodward’s gripe water and a goddess assured for Glaxo baby soap. These were usually large prints on calendars given out as promotional devices and the masses grabbed them as objects of worship.

Besides personal care and baby products, Hindu deities and mythological characters in action (primarily picked from Raja Ravi Varma’s renditions) flooded with consumer goods from cloth, dye to even cigarette (Hawagharri brand from Peninsular Tobacco Ltd) and Swedish safety matches. Large prints of deities that came stuck on fabric bundles from Manchester were given out only with bulk purchase. They ended up being framed and worshipped. Such was their overwhelming charm; the mythological-religious stories were probably the primary preoccupation then, which had so far, never been this vivid, almost palpable.

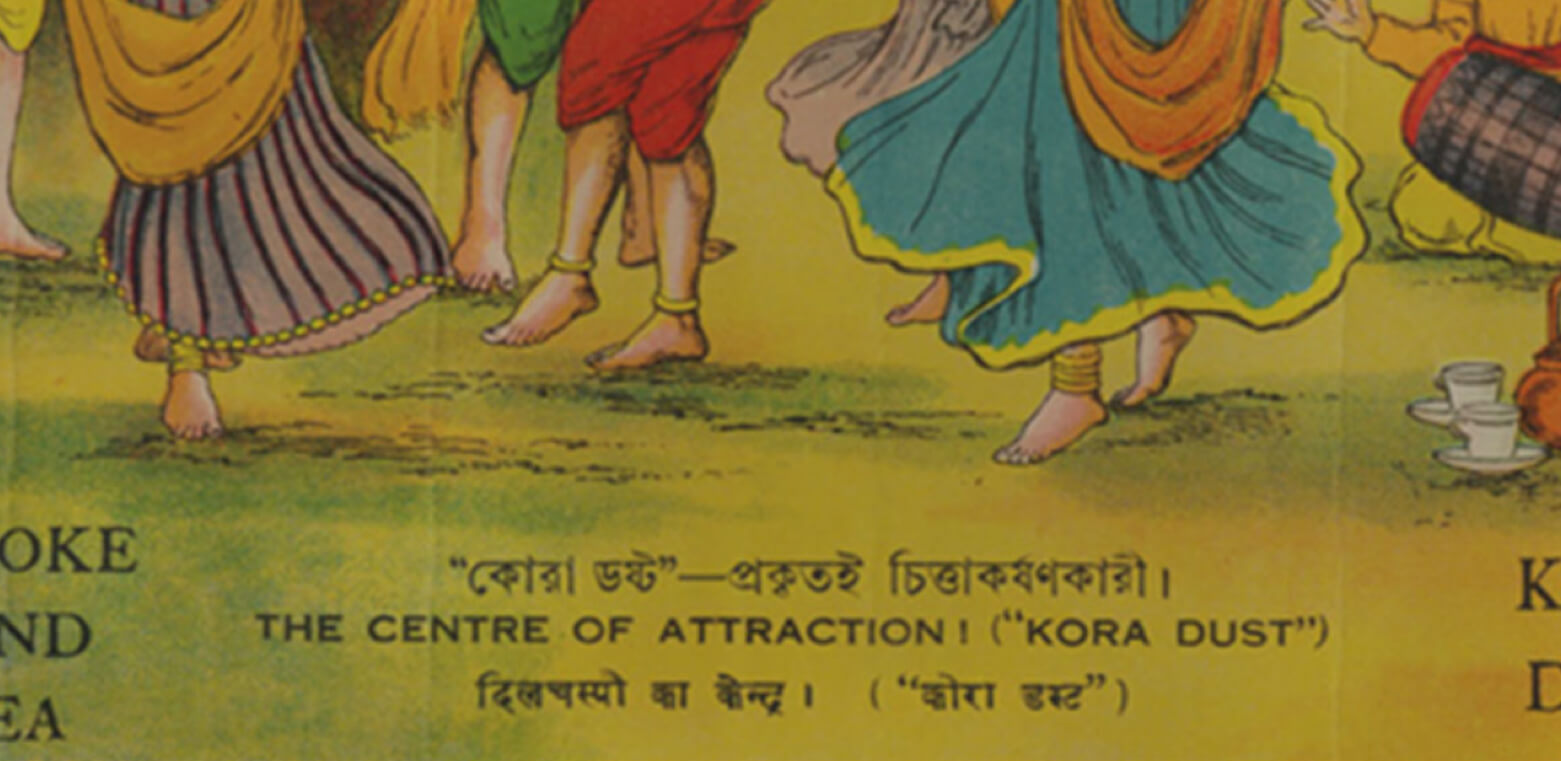

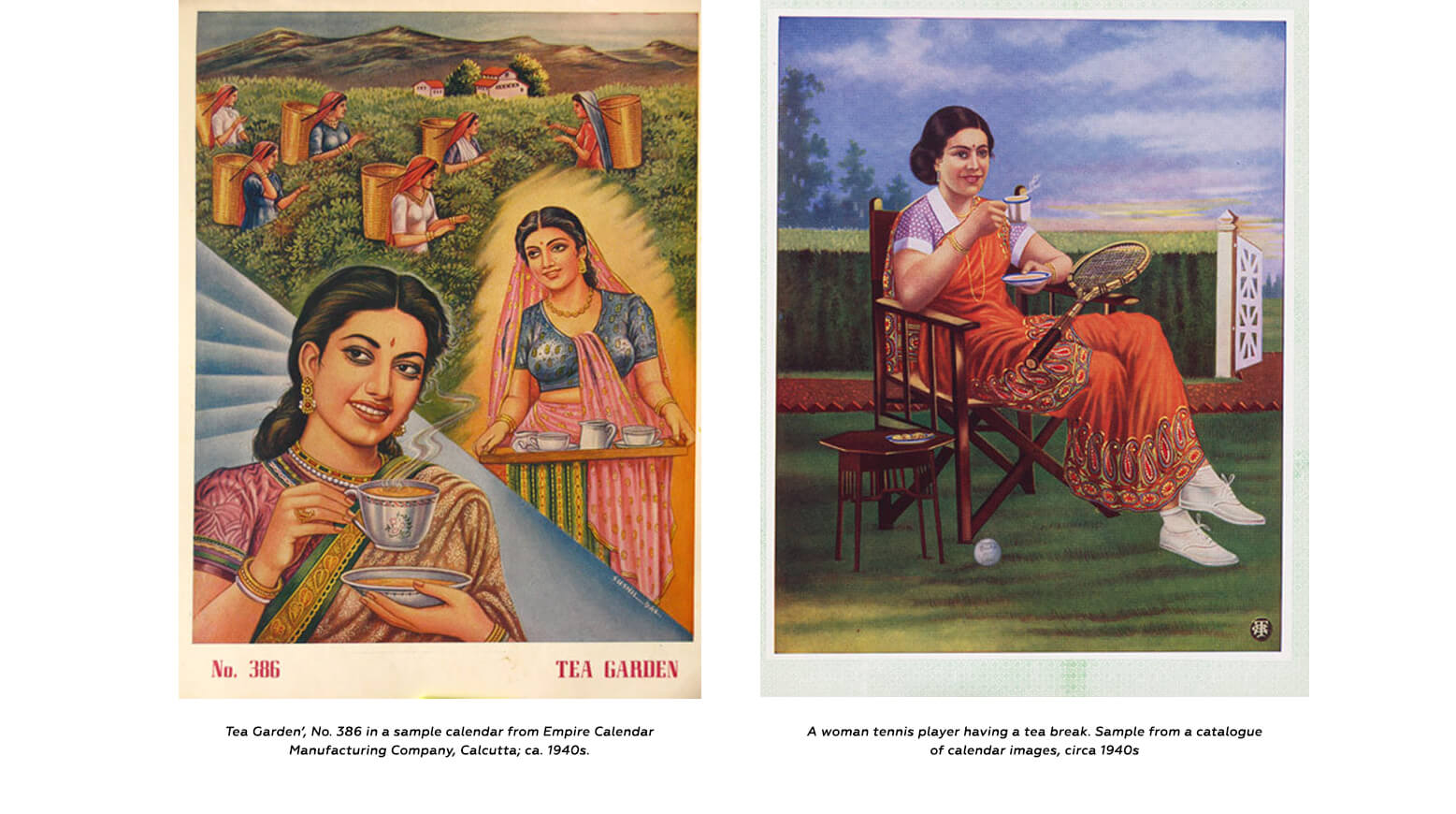

If the popular culture in print a hundred years ago celebrated the sacred, it also gradually set in motion the trends that would follow. Just how Bollywood actresses convincingly speak of green tea (in conjunction with massive PR), early communication depicting the particularly English beverage with brown skin weaved the myth of tea always having been Indian. After the saturation of the British and American markets, the Indian colony was craftily taught the tea ritual with visuals that seeded in one’s subconscious. Those are popular brands even today.

Along with products (riding on monies and businesses), the visual culture influenced etiquettes, styles and behaviours en masse. Almost instantly the predominantly Parsi way of draping a sari became the norm, pan-India modern (even today’s) style of wearing a sari. These caught up with several print advertisements that created the image of the modern Indian woman – a sari clad, shoe wearing, pearl adorning lady – with a 19th century tennis racquet or a cigarette in hand.

The printed visuals circulated wide and far re-defining fashion, modeling Indian cinema (remember the black and white stars of yore?) and setting the mark for the foreign as modern and aspirational.

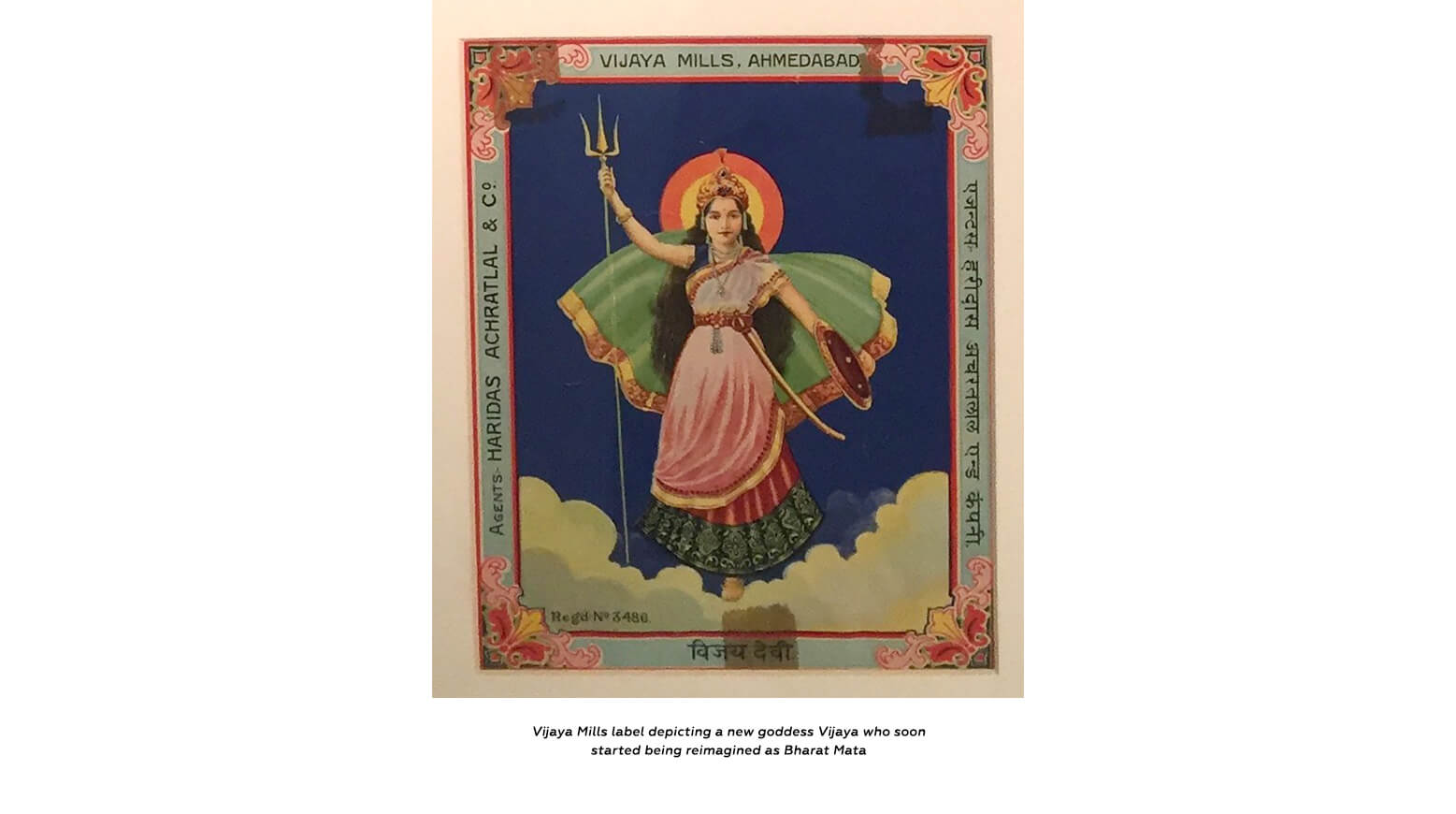

But at the same time the imagery ended up rendering itself to the nationalistic movement. The country was simmering with the struggle for freedom – Swadesi caught up and rampant printing galvanized Indian sensibilities. Soon goddesses started being depicted closer to what we recognize today as Bharat Mata – on the same fabric bundles that once depicted Goddess Lakshmi and Shaivite tilak. Closely entwined is the beginning of the singular story of Hindu identity that went on to define the majority belief as early as the mid-1800s.

These visuals and their retrospective importance to the idea of building modern India are lost in dusty antique garage stores. Few of us today, are perhaps luck to have seen a tin box or two with elaborate printed art in our grand mothers’ cupboards.